Ani Toidze - Still They Paint

10.09.-19.10.2025

Text by Gia Edzgveradze

“The arm with the sword rose up as if newly stretched aloft, and round the figure blew the free winds of heaven.” - “America”, Franz Kafka (Chapter One)

With what chillingly purified image Kafka substituted the rather banal icon of the Statue of Liberty! Perhaps here Kafka also perceived woman’s victory over the patriarchally interpreted Logos, which should be understood as the triumph of feminism!

Chapter One

“Shut your eyes and see!” - James Joyce, Ulysses, Episode 3, “Proteus”

Ani Toidze is an entirely authentic creator, meaning that the fundamental and primary impulse of her work cannot be found within the territory of culture. Her text emerges with natural spontaneity from beyond culture - and this is always,in general, the most powerful charm of creation. At such moments, something is produced that demands recognition, for here the paradoxical nature of being prevails the recognizable cultural code. For the culturologist, her works - as a semiotic territory of suspended signifiers - are a goldmine. For the postmodern philosopher, Ani’s work will appear as a version of the maximalist dream of “third-wave” feminism realized. Ani’s text is indeed a fertile attempt to rupture the content affixed to the historically patriarchal image of woman, thereby brushing against the radiance of Being itself.

In Ani’s art, the Heideggerian locus (the place of Being) is approached from a woman’s version of the path. Atransitional territory thus becomes visible, where woman slips free from the patriarchal interpretation of logos, and consciousness succeeds in liberating itself from this interpretation’s total dominion. The ultimate aim of such an emigration from the territory of mere existence is always the desire to dwell within the unconditionally open space of the ontological. What remains hidden to man appears overtly in Ani’s works. The strange space she creates is terrifying and startling for masculine nature: here, woman has taken the groundlessness characteristic of ontological space as thenatural given of her being, and has established this lostness as her immediate homeland.

In her paintings, the actant is always the woman. Yet this startled being never frets, never panics, never falters - her astonishment before the unconditionally open space is more an exhilarating marvel than a bewildering incomprehension.

Ani achieves her re-interpretation of the patriarchal logos through a profoundly feminine text, corresponding to whatHélène Cixous called écriture féminine. In such texts, one will not find phenomena of hierarchy, subordination, metaphysics, competition, or authoritarianism; nor precise meanings of objects, events, or circumstances. And if such meanings do appear, with Ani they are caught in such a peculiar void that all context is drained away. Suspended as pure phenomena, objects and events may blend into one another or fall into absurd communication with other, equally suspended givens.

These uncanny combinations in Ani’s paintings not only astonish the viewer but awaken in the heart a passionate bliss -the bliss of participating in emptiness. This is the effect of space- light, the central mark of the ontological, which the viewer experiences for the first time, kindling the desire to dissolve into such a space.

Ani’s paintings are saturated with the anatomy of meditation. Purified and hyper-generalized signs, codes, exalted anddetached gestalts prepare us for an approach toward the sacred height and impel us toward the boundless possibilities of reflection. Ani proposes the return of the feminine into the original purity of signs, into fundamental repose.

Everything in her art seems recognizable, yet each thing is stripped of its cultural function, suspended in the tranquildelight of an open meta-space. All demands de-formation, to exist solely as part of the overarching space-light.

Objects, feelings, and situations exist only as signs carried into unconditionally open space and as segments that build this very space. They seem to say: Once we were the darkness of existence, but now we are here, weightless! Nonexistent road signs, animals turned into black stains, mere animals or their skulls, deep loose shadows scattered along the floor of airy space, drifting from canvas to canvas and registering the “Platonic shadow-side” of the world - all these givens, transported from the territory of existence into Ani’s de-bordered space of Being, are trapped like strange but harmless metastases, turned into purified, innocent toys. Yet their innocence recalls those days when they nearly appeared as instruments of torment within the ontic dimension of our daily bodies.

In Ani’s works there stands a strange, transcendent coziness. It resembles swaying in a hammock strung between thegaping fullness of Being and the idea of Death - an odd mixture of freedom and vulnerability. It is precisely through this sensation that one may encounter what could be termed transhumanity.

Yet the entire semiotic richness of Ani’s visual narration, even the refined weave of these meanings, has no decisive significance compared to the one essential, determinative message she offers to humanity. This message crowns everything described above like a diadem, conditions all meanings, draws the viewer into a voluntary current of self-surrender, and with stealthy calm promises the coming of some unknown grandeur. This all-determining, all-absorbing, blissfully annihilating force is space-light, the salt of Being, so furtively revealed in Ani’s works.

What is this space, what does Ani tell us here? There are many types of space - cultural, spiritual, political, and so on. No - Ani does not fragment herself into segments. What arises decisively in her work is the space of ontological openness, the fullness of Being itself, into which the feminine principle, protected from patriarchal contamination, has penetrated. Everything that once actively participated in symbolic orders and ontic space is here immobilized, while even the laughter of a smiling girl is silent. Such muteness annuls history itself. All is steeped in unconditional openness- where every next step of objects or humans becomes critical, for openness means total dissolution. This is the prospect of Ani’s works. The maw of Being’s space-light gapes open, and everything we once perceived as witnesses ofexistence floats within it - soon to become light-space itself. Thus stands the transcendent tension of Ani’s work: tension without torment, expectation of conclusion suffused with bliss.

Chapter Two (A Message to Georgians)

“Shut your eyes and see!” - James Joyce, Ulysses, Episode 3, “Proteus”

What, then, is particularly valuable for Georgians in what Ani offers through this exhibition? Let us consider: it is a well-known and striking fact that Georgians do not engage deeply with the sea - this is inscribed in the patterns of Georgianconsciousness and is a defining trait of the Georgian gaze. A Georgian may wade into the sea for a few meters, forplayful splashing, but the open vastness of the sea rarely commands attention. Though Georgia has an extensive coastline, it has never inspired the construction of ships or a fascination with the conquest of this open space. In Georgian perception, the phenomenon of the sea as boundless space essentially does not exist; its unspoiled openness holds no attraction.

Instead, Georgians are drawn to mountains. Mountain landscapes are segmented: the vast slopes carve the sky intodramatic, monumental compositions. Here, the sky offers relief and serenity but never a rupture. The sea, in contrast, represents a perilous phenomenon of pristine openness, beyond the constraints of measured boundaries. In such a space, the human being confronts their essential nakedness - only in the face of such absolute openness does true vulnerability emerge. It is precisely this exposure that Georgians avoid when engaging with the sea, retreating from the demanding, totalizing nature of such space.

Ani’s spatial compositions in her paintings offer a deconstruction of the symbolic order and the enactment of fully realized “poiesis.” For the Georgian viewer, this may be difficult to apprehend; they will need to close their eyes.Contemporary Georgians are not accustomed to artifacts that carry such expansive generalizations. By nature, they inhabit a small-scale, intimate mode of being. Daily life has long been stripped of extreme or maritime experiences. TheGeorgian lives in a small country, in a small household, both of which he once defended steadfastly and bravely. Yet for the past two centuries, ambition and the drive toward transgression have been removed from his daily life. Comfort occupies the center of his worldview, and the longing to engulf the world, a sense of its overwhelming presence, is a scent his soul no longer recalls.

Ani’s works, in contrast, offer a transit toward ontological openness. They present a stark challenge to the Georgian viewer, a call to confront the luminous emptiness of boundless space, a silent demand for the surrender of ego and immersion in radical perception.

Chapter Three (References from Culture)

“Shut your eyes and see!” - James Joyce, Ulysses, Episode 3, “Proteus”

The question of discovering variations of total space has been posed repeatedly across art history. Within culture and human consciousness, the manifestation of such spatial awareness has been most recently and grandly offered by American artists. In Abstract Expressionism, every element of a painting serves to reveal the totality of space. European art, by contrast, often constructs spiritual or cultural dimensions with painstaking detail; nowhere does it articulate the raw, comprehensive decree of openness through which our perception of the world is transfigured, dematerialized, and infused with insight from a pure origin. Such a space becomes the most potent and liberating.

In American art, private, spiritual European spaces are replaced by the idea of spatial totality: Pollock’s canvases fragment infinite dimensionality, expressed through the vibrational fluctuations of overlaid lines; Motherwell’s “Elegy tothe Spanish Republic” tolls a monumental dichotomous bell, instructing the soul on the eternity beyond sound; Rothko’s voids of light and color communicate the purity of universal origin. These titanic explorations of space find their parallel in American photorealism, as in the works of Richard Estes and Chuck Close: Estes constructs massive beams of light reflected and refracted, a supreme abstraction of luminosity, while Close renders topological detail and fractalopenness, together articulating a space both overwhelming and engulfing in scale. Similarly, the spatial light in Hopper’s interiors subverts human-scale culture, demanding immersion into absolute openness.

Ani’s paintings offer Georgian consciousness a similar - yet previously unknown - encounter: a monumental space demanding a sacrificial submission, the erasure of residual structures of existence deposited in the transcendent, and the enthralling absorption of figures and objects into the ecstasy of light-space. They hover under the spell of luminous influence, an immense openness spinning above, inducing profound astonishment in ordinary perception.

Chapter Four

“Shut your eyes and see!”- James Joyce, Ulysses, Episode 3, “Proteus”

Due to this compulsion of space-light, the continued “presence” of objects and figures in Ani’s paintings manifests as a subtle atmosphere of melancholy, nostalgia, and gentle sadness, as if these are their final, farewell moments in the realm of existence. In an instant, all is dissolved into the boundless openness of white space-light (Sanskrit: shuklam) and becomes unconditional freedom. The human figures in Ani’s works are tranquil; it matters not whether they are laughing, exalted, or bearing an expression of deep contemplation - their allegiance to the unconditionally open space-light remains absolute. The revelation of such a connection, and the confrontation of the human figure with space-light, is perhaps the greatest gift one can offer to a vulnerable person. For the Georgian viewer, this constitutes an extraordinary discovery. In a similar way, the aforementioned American artists revealed the experience of eternity to pragmatic Americans, establishing the highest expression of “Americanness”: America as a space of intensely fluctuating light.

It would be valuable for Georgians to reconsider their own identity in relation to the totality of Ani’s space-light, whether in connection to the cosmos or even the highest form of divinity, offering one’s human constitution as a sacrifice to light.

If, in the eighteenth chapter of James Joyce’s Ulysses, such a sacrifice is enacted through the deliberate ritual of raucous noise, thereby unconsciously presenting this most profane act to the West and offering it to humanity, Ani’s gift to Georgians is instead a quiet, muted, and pale whirlwind.

Yet for Georgians, the sea still inspires fear; Ani’s cosmic audacity remains, for now, premature.

-

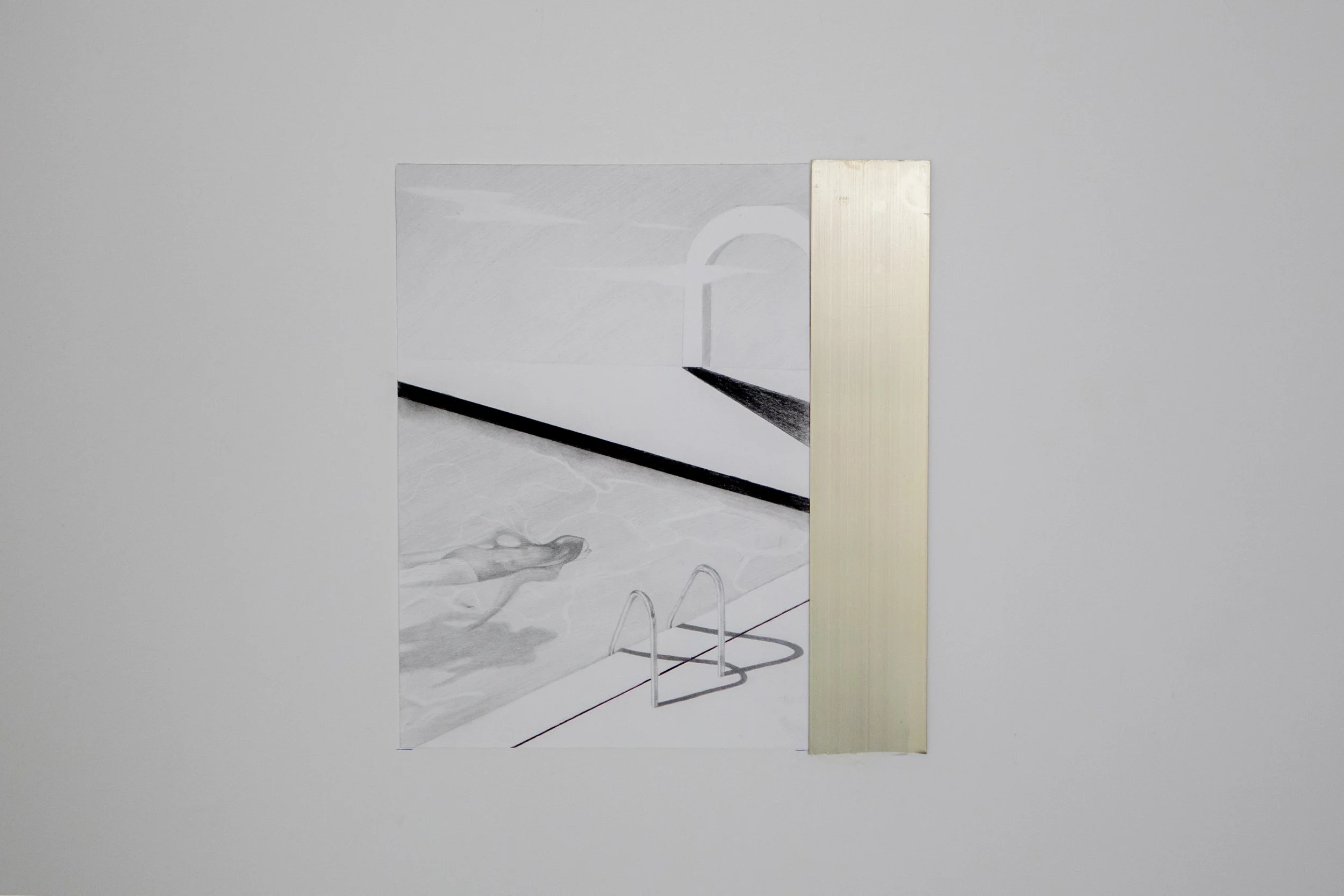

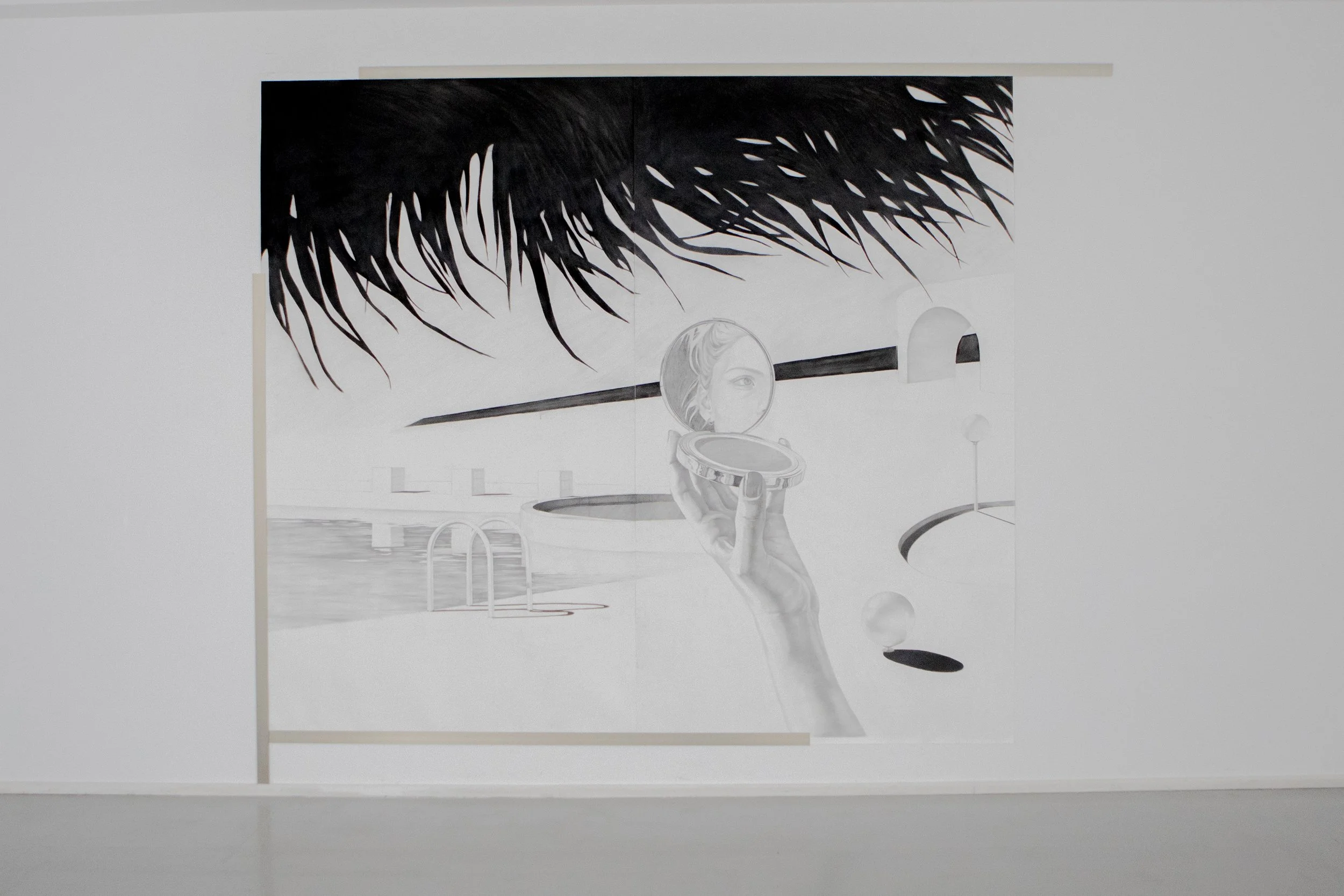

Shut Your Eyes and See

Exhibition View

-

Shut Your Eyes and See

Exhibition View

-

Shut Your Eyes and See

Exhibition View

-

Shut Your Eyes and See

Exhibition View

-

Shut Your Eyes and See

Exhibition View

-

Shut Your Eyes and See

Exhibition View

-

Shut Your Eyes and See

Exhibition View

-

Shut Your Eyes and See

Exhibition View

-

Shut Your Eyes and See

Exhibition View

-

Shut Your Eyes and See

Exhibition View

-

Shut Your Eyes and See

Exhibition View

-

Shut Your Eyes and See

Exhibition View

-

Shut Your Eyes and See

Exhibition View

-

Shut Your Eyes and See

Exhibition View

-

Shut Your Eyes and See

Exhibition View

-

Shut Your Eyes and See

Exhibition View

-

Shut Your Eyes and See

Exhibition View

-

Shut Your Eyes and See

Exhibition View

Photographer: Dato Koridze